Do You Know the Messiah’s Name?

One of the challenges for my wife and I in having ten children was names. Besides the fact that my wife wanted to have their names in hand from the moment we knew of their conception, while I tended toward leaving that important decision much closer to their birth, we shared pretty high standards. We preferred characters from the Hebrew Bible, but only those of noble character and they had to be sufficiently easy for English speakers to pronounce. It helped that we didn’t feel the need to provide more than one name per child, though three did get middle names. All in all, we wanted to give our children names that would be meaningful to both to us and to them.

God takes naming seriously. The Bible tells us he invented it, when he called the light “day” and the darkness “night” (see Genesis 5:1). While he would pass on the naming of animals and most people to humans, he would from time to time intervene, providing names to particular individuals either before birth as in the case of Ishmael and Solomon or change them afterwards, as in Abraham and Jacob.

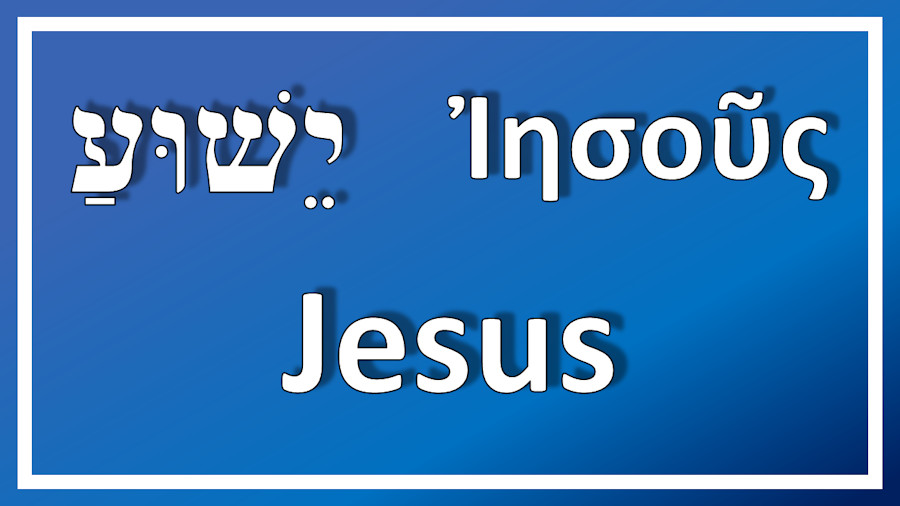

Tragically, the meaning of the most important name God has ever given anyone has been lost to most people, partly due to the English translation tradition. In the great majority of English versions of the New Testament, we read the angel’s words to Joseph the betrothed of Mary as “You shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins” (Matthew 1:21).

To most the name “Jesus” is exclusively associated with the Messiah, which is fine. But the name actually given by the angel was common at that time. The name “Jesus” is an attempt to provide an anglicized version of what is actually recorded in the New Testament. Since the New Testament was written in Greek, it itself translates most of the dialogue and speeches in the Gospels and the Book of Acts from the original Hebrew or Aramaic. The name normally translated in English as Jesus is the Greek Iesous (pronounced yay-soos). But that is not exactly what Joseph heard from the angel. Nor is it what people in his day called him. What God named him was more along the line of Yeshua, a proper name derived from the Hebrew word for “salvation.”

Yeshua is certainly a fitting name for the Savior, and associating his name with the concept of rescue (which is what salvation in the Scriptures means) is most likely intended. But connecting with the concept of salvation is not the first thing that the people of his day would have thought of upon hearing his name. Whether a person regarded him as Messiah or not, Yeshua was and is the common short form of Yehoshua, the Hebrew name normally rendered in English as Joshua – the same name given to the son of Nun, the successor of Moses and the military leader who led the conquest of the Promised Land. It is still common in Hebrew today to refer to people named Yehoshua as Yeshua. That said, it is almost certain that the New Testament Greek derivation Iesous may not be representing the short form, Yeshua, after all. That’s because the name Iesous is used in passages referring to Joshua the son of Nun, thereby following the lead of the Septuagint, the early Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, where Joshua is translated as Iesous.

This is all to say that when God named the Messiah it was clear that he would be associated with Israel’s prototype military leader who led the conquest of the Promised Land. As people came to consider the possibility that this Joshua might be the Messiah, it fueled their expectation that he had come to engage in a new conquest of the Land. Instead of overcoming “the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites” (Exodus 3:8), this time it would be the vanquishing of the Romans.

For most of the time since returning from Babylon centuries earlier, the Israelites were under foreign domination, a certain sign that they were the objects of God’s disfavor. Messianic expectation became associated with the restoration of God’s favor and the end of foreign oppression. By God naming the Messiah “Joshua,” he affirmed their expectations.

Yet the last thing we think of Jesus is his being a conqueror of the likes of Joshua son of Nun. What is often taught is that the messianic expectation of the first century Jewish world was wrong. Jesus didn’t come to conquer in that way, rescuing the people from military and political oppression. Rather, he came to save in a spiritual, nonphysical sense.

Obviously Jesus did not aspire to or fulfill the role of a military conqueror. There was much about his methodology that was contrary to expectation. We see this in Peter’s reaction to Jesus’s announcement to his closest disciples of his imminent arrest and death (see Matthew 16:21-23). That Jesus also mentioned resurrection seemed to go over Peter’s head, since suffering and death was so counter to the Jewish messianic concept. However, just because the Messiah’s methods were contrary to expectation doesn’t mean he is any less the conqueror. God didn’t stamp his Chosen One with the name Joshua only to dash the people’s hopes and dreams that he himself gave them through their prophets.

Some see the misunderstanding solely in terms of timing. Much of what was expected two thousand years ago will happen when Jesus returns. In the meantime, God is patient with humankind as he gives us the opportunity to turn to him. But one day, the Messiah will return to judge (see Acts 17:31). The problem with shifting the Joshua concept to later is that it neglects the power of everything he has done until now.

Calling him Joshua is not a shout out to a future time, it’s the Messiah’s God-given identity marker. It’s not that he will one day be a Joshua, who will conquer evil’s minions and establish God’s rule on earth forever. He will indeed do that fully and completely upon his return, but he has been the conqueror all along. As the greater Joshua, he has conquered far more powerful threats than the earlier Joshua ever faced.

The Jewish world, Jesus’s followers included, thought he would beat off the Romans, but instead he beat off sin and death. This is not a spiritual-only victory. It’s spiritually based, but not spiritual only. This Joshua may have not removed the Roman presence from ancient Israel. He did something far more effective. By defeating death, he broke Caesar’s power, thus freeing God’s people to conquer the effects of sin throughout the world.

Coming to grips with the essence of his God-given name is essential to effectively follow him today. His followers are increasingly relegated to society’s fringes. The aggressive tone of our culture’s influencers can be overly intimidating. But it is the people of the messianic Joshua who have been mandated by God to teach the nations the Truth about himself and his ways. This is not a time to shrink back. Instead, we need, like his early followers, to pray for boldness and the demonstration of his power (see Acts 4: 23-31). As he answers this prayer, let us step out in confidence, knowing he will prevail.

Scriptures taken from the English Standard Version

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!