Escaping the Ideological Snare

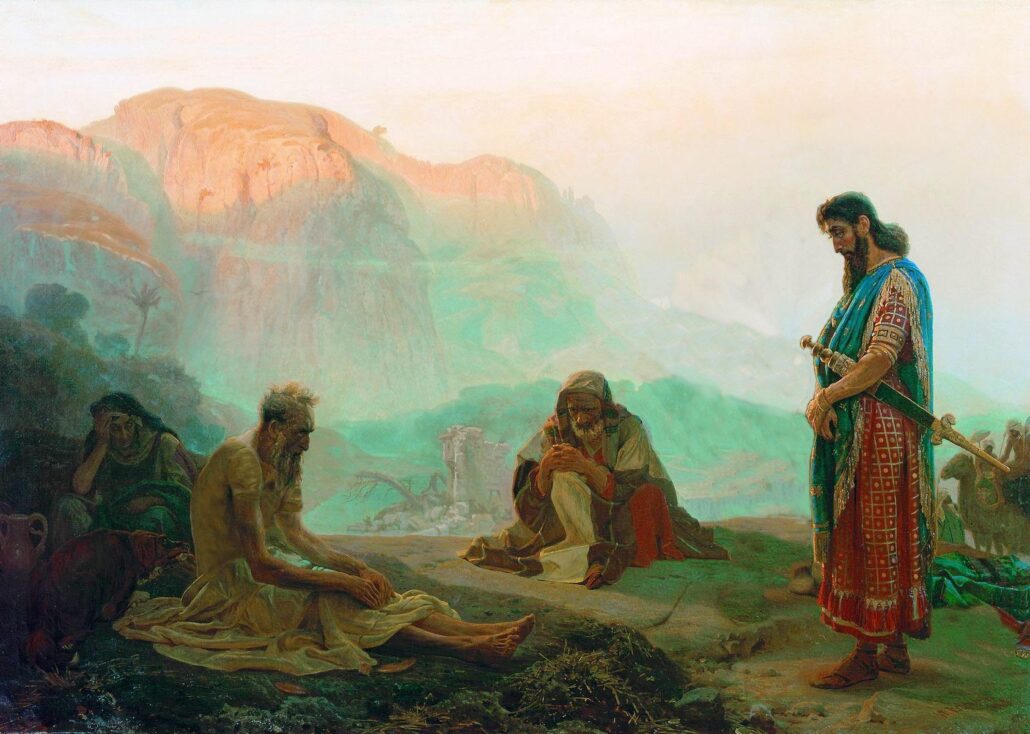

“Job and his Friends.” Painting by Ilya Repin (1844–1930). Public domain

I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. “Who is this that hides counsel without knowledge?” Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know. (Job 42:2-3; ESV)

In my desire to more fully understand and teach the Bible, I am keen to unearth the ways we approach Scripture that undermine its effectiveness. There are all sorts of popular misconceptions that stand in our way of being fully exposed to God’s Truth. I list nine of them in my first publication, “Undermining Forces” (book information available here). One reader asked me to write a fuller version outlining antidotes to each one. Good advice. Maybe I will one day, but I keep finding more, including this really big one I want to share with you now (and its antidote).

I don’t know how familiar you are with the Book of Job (pronounced like “robe” not “lob”). It’s part of the Old Testament’s wisdom literature. It is written primarily in poetical form, except for its introduction and conclusion, which are narrative (story-style). Job the man is very rich and genuinely pious, a quality God himself boasts about in his heavenly court. The Accuser (Hebrew: the satan) challenges God, claiming that Job’s piety is exclusively due to his wealth. Take his stuff away and he would certainly curse God to his face. God grants permission to the Accuser to wreak havoc upon Job’s life, as long as he doesn’t touch the man himself. Job then experiences a series of devastating disasters and is left destitute and childless. Yet he responds with humility and faith. The Accuser is not satisfied, however, and makes a case that as long as Job’s life itself is intact, then his continuing to love God is no big deal. God responds to this second challenge by allowing the Accuser to strike Job as long as he doesn’t kill him. Job’s suffering is the stage upon which the rest of the story is told.

Job’s body is in anguish, covered in boils, but he still refuses to curse God. Note that he doesn’t know about the heavenly contest that is at stake. All he knows is that he is suffering badly and for no apparent reason. Three friends of his come to sit with him. A whole week goes by in silence, and then Job finally speaks. He claims his plight is unjust. His friends don’t agree and take him to task. The latter arrival of a fourth friend bridges the debate away from Job and the others to God himself. God’s subsequent lengthy speech puts everyone in their place, but never explains what was going on behind the scenes. In the end, Job’s fortunes are restored.

The most common understanding of the Book of Job is that it is a treatment of the theological and philosophical problem, “Why do good people suffer?” That theme is certainly in the book. It’s an important and difficult question that the book handles ingeniously. But if Job is simply about unjust suffering, why all the speeches? Does it really serve this purpose to have the suffering virtuous man go on and on about his innocence? And then for him (and us) to hear his supposed friends also go on and on about why Job is wrong, that he must have done something to deserve this. Their accusations grow increasingly arrogant and misguided. Certainly, God’s appearance towards the end is a highlight, and the need to trust him in spite of appearances, no matter how dismal, is an essential lesson for all of us to learn. But is that it?

The real problem that Job and his friends have is one of the most common for both believers and non-believers today. And it seriously undermines any attempt to truly grasp Scripture in its fullness. The issue of unjust suffering in the story is functioning as an example of a much more encompassing problem. What is it? Our unwillingness to properly relate to things we don’t understand. What everyone, except for the heavenly gathering, didn’t know was what was going on. Job and the others, while dealing with the situation in different ways all had this in common. They believed that the world worked a certain way. For Job’s friends the only conceivable reason for what was happening to Job was that he was a bad guy. Even though they knew about his good reputation, and they had no evidence to the contrary, Job’s suffering could only mean he had seriously sinned. They had no room whatsoever to even consider that something outside their understanding was remotely possible. That’s why the more Job claimed innocence, the more they demonized him.

Job’s friends were in a philosophical box which they couldn’t get out of. Whether they understood the dynamics of this or not, they were deeply committed to a particular understanding of how life worked. It included a permanent filter through which to interpret human suffering that allowed no exceptions. The only way for them to cope with the pitiful sight before them was to continue to spout their ideology.

An ideology is “a comprehensive set of normative beliefs, conscious and unconscious ideas, that an individual, group or society has” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideology). In this regard, Job wasn’t all that different from his friends. He also believed that people suffer because of wrongdoing. However, a couple of factors were at play to release him from this ill-informed ideology. First, his integrity enabled him to not doubt himself. If he would have allowed the prevailing ideology to continue to determine his understanding of life, he may have forced himself to confess something – a twisted version of reality or something completely imaginary. If he would have done so, the ideology would have remained intact and the tension with his friends reduced. Second, he was indeed a faithful man of God. So, in spite of the confusion, he knew to go to God for answers. That he challenged God to a court battle he thought he could win, while misguided in some ways, at least demonstrated that in spite of his ideology, he knew deep down who was the only one who could rectify this terrible situation.

So much of the culture clash of today is a clash of ideologies. Don’t think for a second that Bible believers are immune. Far from it! I am not saying that Jesus followers are necessarily left- or right-wing ideologues, though that might be. It’s far more prevalent than we might think. However it might be said, it seems to me that many, if not most, believers define their faith, not in terms of Bible, but some sort of comprehensive theological, denominational, or philosophical set of principles, an ideology in other words.

But isn’t biblical Christianity an ideology – God’s ideology? Doesn’t God’s Word provide us with a comprehensive set of principles and a divinely oriented philosophy of life? Yes and no. Biblical truth is indeed sufficiently comprehensive. It provides us with everything necessary to live effective, godly lives. It sufficiently addresses every area of life. It establishes priorities, focus, and meaning. But is it an ideology? A book that’s daring enough to include Job is no ideology. Instead it undermines ideology. It reminds us that our systems of thought, no matter how comprehensive, supposedly helpful, and apparently biblical, have significant gaps. We often don’t know what those gaps are until we find ourselves in crisis. But when crisis comes, the Bible is clear – and not just based on the Book of Job – relying on our principles should never come before relying on God. If our Bible understanding doesn’t continually lead to us to dependency upon the Master of the Universe, it is seriously deficient.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t attempt to understand the Bible or avoid making theological assertions. It also doesn’t mean that we must avoid giving definition to our particular faith communities and affiliations. Definitions, clarifications, and policies need not be ideologies. If the Bible is our authority for faith and practice as it should be, then we need to allow it to challenge our convictions and preferences. Molding Scripture into our particular ideologies, however they came to be, however precious they are to us, blinds us to its truth. If we don’t approach it with the level of humility exemplified by Job, we will become more and more like his good-for-nothing, so-called friends.

The example of Job’s humility is not solely found in his repentant state near the end of the book but is demonstrated throughout his ordeal. Like Jacob, he too wrestled with God, refusing to let him go until he blessed him. Allowing ourselves to engage God on core issues can be very painful. Of those things we hold dear it isn’t always easy to discern what is of God and what is of ourselves. We shouldn’t shift and adjust our thinking every time a new idea in the name of the Lord comes along. But at the same time, do we need to wait for a Job-like experience before we submit our ideologies to God and his Word? It can be scary to lay down our ideologies, but the deepening reality of God that will be ours if we do is more than worth it.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!