The Bible and the West Bank

Bethlehem as seen from the Gilo neighborhood of Jerusalem

Download Audio [Right click link to download]

An unsettling view

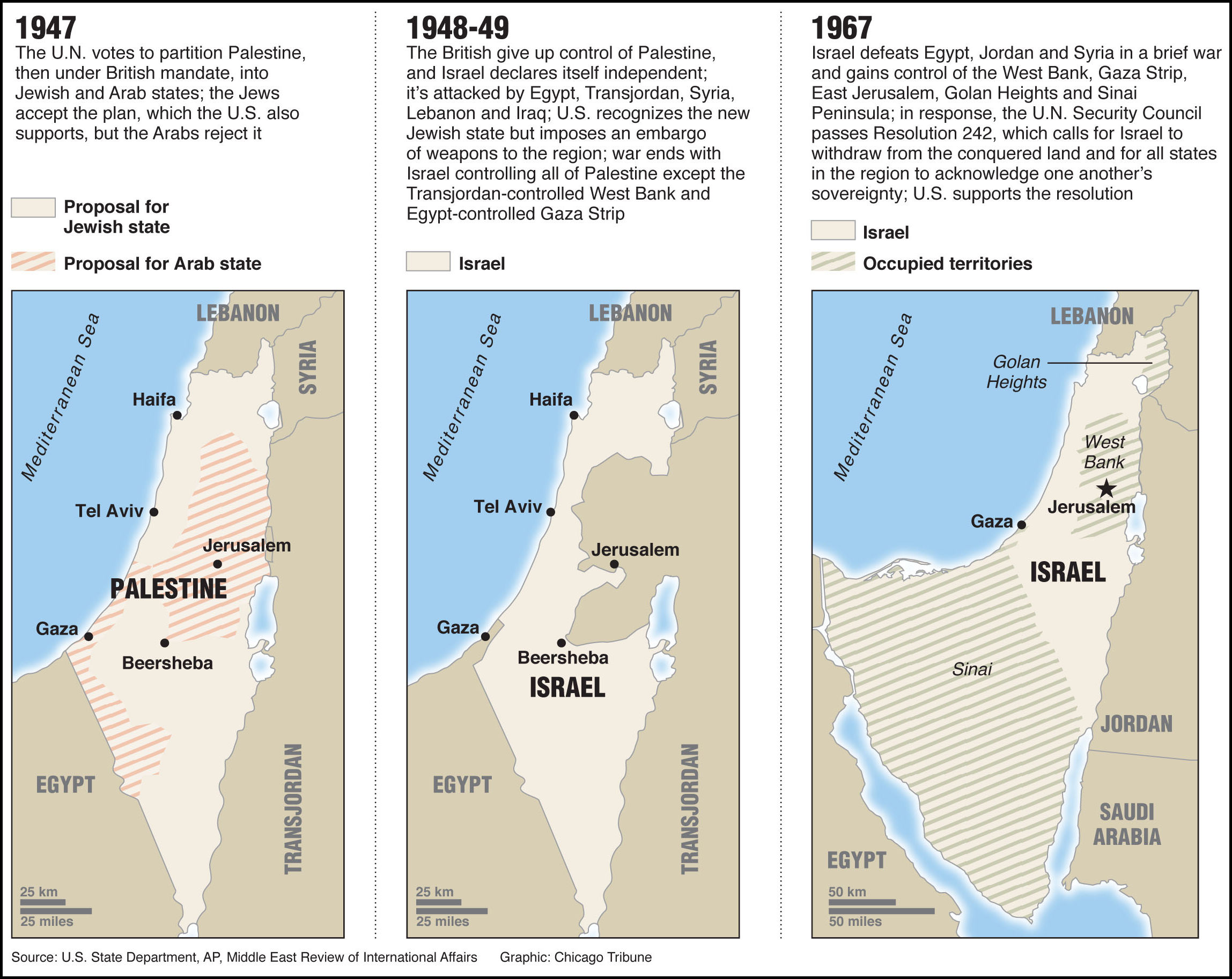

This past September, I was standing on the balcony of my friend’s house in Jerusalem. From there, I had a great view of Bethlehem (pictured above). I just stood there and stared, trying to take it all in. The neighborhood we were in is Gilo. Before 1967 and the Six-Day War, this was Jordan, not Israel. My friend pointed out a house down below. The owner was born before 1967. He has a Jordanian passport. That’s because Gilo is on the other side of the “Green Line,” the 1949 armistice line, written with green marker at the end of Israel’s War of Independence.

Following the Six-Day War, Israel annexed Gilo, making it part of Israel proper as it did with the rest of Jerusalem. The world community, on the other hand, regards Gilo as an illegal settlement, like all the other Jewish settlements in the West Bank. Standing on that balcony, aware of the disputed status of the neighborhood, I felt agitated. While I fundamentally support the State of Israel, I was unsettled by world opinion.

Policy shifts

Last month, November 18, 2019, US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, signified a shift in the State Department’s policy toward Israeli settlements in the West Bank, when he announced: “The establishment of Israeli civilian settlements in the West Bank is not per se inconsistent with international law.” The very next day, the United Nations overwhelmingly passed one of its one-sided anti-Israel resolutions that deems Israel as occupying Palestinian territory with no reference to Palestinian responsibility. Surprisingly, and marking its own policy shift, Canada supported the anti-Israel resolution, thus regarding the settlements, including where I was standing in Gilo, illegal.

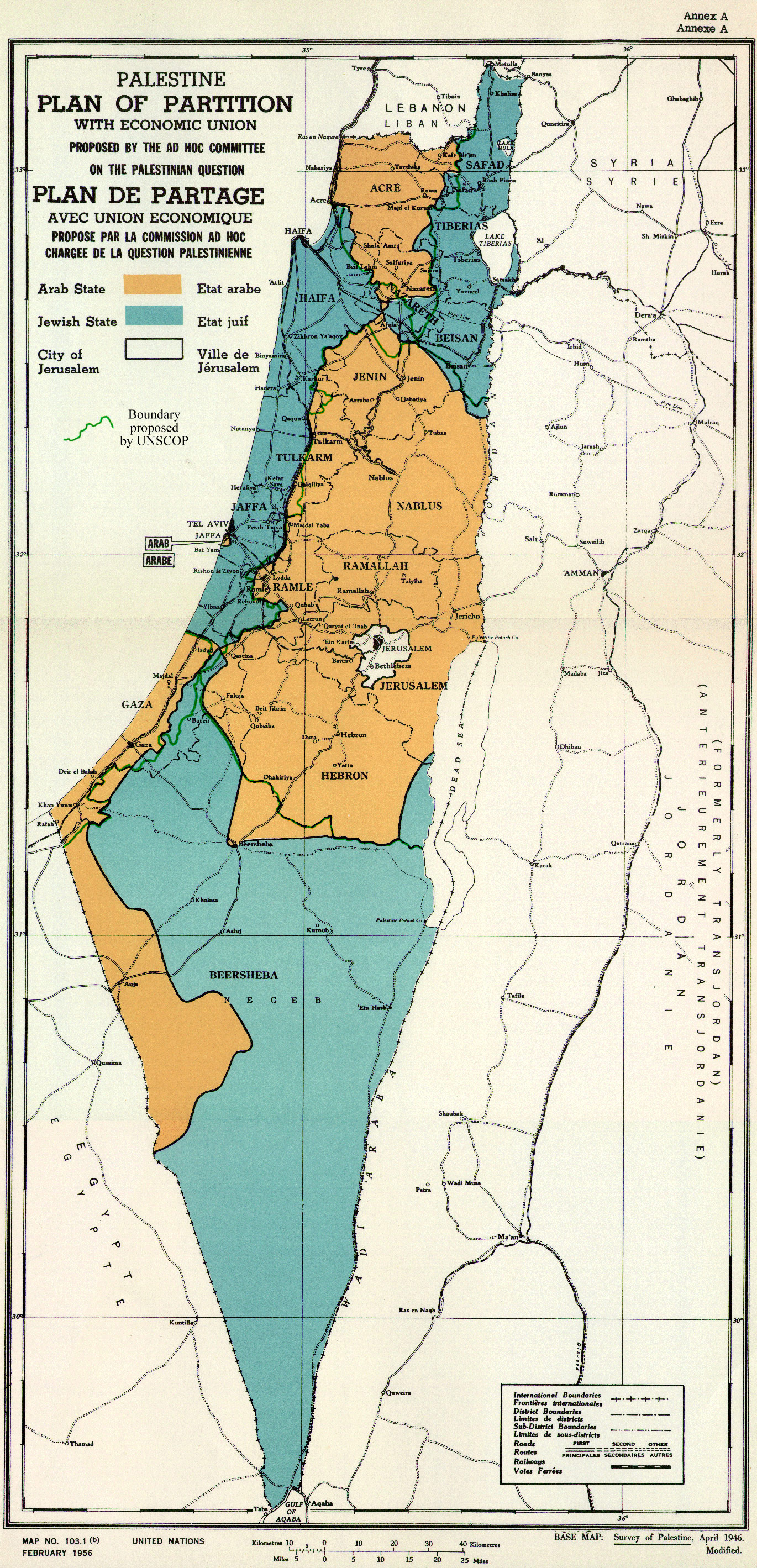

The technicalities regarding the legal standing of the West Bank are far more complicated than what many think. The West Bank, a Jordanian designation for the biblical territories of Judea and Samaria, wasn’t intended to be part of Jordan. Jordan annexed it after capturing it in the Israel War of Independence. Under the UN Partition Plan of November 1947, it was proposed that the region was to be part of an Arab Palestinian state; that is, not Jordan, but a state for the Arab Palestinians living in the land, as opposed to the Jewish Palestinians (as they were then called). The term “Palestine” in those days had no ethnic connotation; it referred to the region as inhabited by Jews, Arabs, and others. The UN Partition Plan was passed by the UN and, in spite of the Arab world’s rejection of it, became the basis of the Palestinian Jewish settlement’s declaration of independence. Ironically, there was no outcry following the Jordanian takeover of the region as a part of the War of Independence; no outcry over the exile and murder of the residents of the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. And yet, in June 1967, when Israel recaptured the Jewish Quarter as well as Judea and Samaria as part of the victory in a defensive war and was once again able to establish a presence in their ancient homeland, almost the entire world deemed it illegal.

I find it hypocritical that a country such as Canada can pass judgement on Israel when so much of our population enjoys the fruits of colonization. It is now popular, especially at public gatherings, to acknowledge the historic connection of a locale to the indigenous people who may have lived there centuries before. How they can be certain who the actual original people or peoples were, I don’t know. Be that as it may, in spite of these acknowledgments, to my knowledge, there is no attempt among Canadian governmental leaders to restore these lands to their original inhabitants. Neither has the UN passed a resolution declaring the Canadian Parliament, for example, and other such settlements, illegal.

So much more could be said about the historical, political, and social issues relating to Israel and the West Bank. Understanding such issues are essential to developing a helpful perspective on a most difficult conflict. But as I stood on the balcony in Gilo, more than any of this, I longed to grasp what God thought.

Christians support of Israel

Some Christians express unwavering support of Israel as the national home of the Jewish people. However, in my experience, most people who identify as Christian are either ambivalent or uncomfortable with making any connection between their faith and current issues surrounding the “Holy Land.” They are happy to make a religious pilgrimage to the region where the vast majority of Bible stories happened and “walk where Jesus walked.” Beyond that, modern Israel isn’t any more relevant to them than any other country.

These Christians may take the Bible very seriously yet regard the contemporary land of Israel as having no practical and ongoing relevance to their lives or their theology. They may affirm that Israel the people and Israel the land are central to the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament), and yet take Jesus’s fulfilment of Old Covenant expectation as a transformation of national and geographic issues to universal spiritual ones. The land of Israel becomes nothing more than an ancient stage upon which to learn grander spiritual truths.

Those Christians who support Israel tend to simply point out the very many land promises God gave to Israel (e.g. Genesis 12:7; 13:15; 17:8; 16; 25:1-6; 26:3-4; 32:28; 35:12). Apart from treating the land promises of Hebrew scripture as still relevant, they may point to a New Testament passage such as Romans 11:29 (“For the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable.”) as evidence of God’s ongoing plan for the Jewish people, including the land promises.

The messianic connection

It seems to me that one of the reasons for many Christians’ resistance to the idea that the whole Bible consistently and unequivocally supports the ongoing Jewish divine claim to the land is that it doesn’t seem to have any connection to the centrality of Jesus as Savior. Many believers would agree with the sentiment recently expressed to me by a pastor who said something to the effect that the entire Bible is about salvation. Others term this as “it’s all about Jesus.” As someone whose life has been radically and wonderfully transformed by how the Scriptures vividly point to Yeshua, I understand the emphasis, but there is much more to the Bible than it’s functioning as a spiritual device to create a saving transaction between God and human beings through the Messiah.

The Bible is God’s written revelation to equip us to live effective godly lives (2 Timothy 3:16-17). This begins with and is sustained by a right relationship with God through trusting in his Son. But that’s just the beginning. The Bible also provides all we need as the basis of how to live life as God intends. Genuine, biblically informed, godliness requires gaining God’s perspective on the world in which we live, including understanding God’s relationship to Israel and the Land. Core to this is the direct connection between Jesus and the land promises to Israel.

Genesis chapter fifteen is well-known for the doctrine of justification by faith. In response to Abram’s concern that, due to his being childless, any inheritance he might have would eventually go to his servant, God clarifies that he will indeed have a son of his own. In fact, he was to have innumerable descendants. In spite of his current state, Abram trusted what God said, which in turn was counted to him by God as righteousness (see Genesis 15:6). But that’s not how the passage ends. In the very next verse, God reiterates the promise of the land. Note how he does it: He directs Abram to offer a special sacrifice, so he laid cut up carcasses of animals on the ground. Abram fell into a deep sleep in which God spoke to him about his descendants’ future bondage in Egypt, eventual release, and land acquisition. Then he saw (either in the dream or awake) a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch passing between the carcasses followed by these words: “On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying, ‘To your offspring I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates, the land of the Kenites, the Kenizzites, the Kadmonites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Rephaim, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Girgashites and the Jebusites’” (Genesis 15:18-21).

This scene depicts an ancient custom of covenant making. The Hebrew for “making a covenant” is actually “cutting a covenant” most likely due to a custom such as this. It appears that when two parties cut a covenant in this way, their walking together between the pieces of the sacrifice was to illustrate that if either party fails to uphold their part of the covenant, then a plight similar to that of the carcasses was to befall them (see Jeremiah 34:18). However, in this case, Abram didn’t walk along with God. Instead God (illustrated by the smoking fire pot and flaming torch) walked through the pieces alone. Abram was to surmise, therefore, that if ever he (or his descendants after him) in any way betrayed the covenantal arrangement between him and God, God alone would suffer the consequences. Whether or not Abram understood the implications of what he saw, there is no doubt that God’s promise to him and his future offspring regarding the land was solemnly guaranteed by a pledge of God’s own life, so to speak.

Apart from the insight God gave Abram concerning the future plight of his offspring (see Genesis 15:13-16), Abram knew little of the complexity of the development of Israel—particularly the covenant given them through Moses at Mt. Sinai. He knew nothing of the specifics of how they would acquire the land under Joshua or the struggles they would face in the subsequent centuries. He didn’t know that his people would be eventually judged by God due to their unfaithfulness or that this judgment would include exile from the land promised to them through him. Yet Israel’s failure to be true to its calling as God’s chosen nation could not result in the absolute loss of the land. For God guaranteed otherwise by pledging to suffer the consequences of Israel’s failure. This he did through the Messiah when he died on the cross.

Readers of the New Testament rightly understand Jesus’s sacrifice for sin as the vehicle through which human alienation from God is resolved. What we have missed is that core to this sacrifice is God’s commitment to Abram and its direct relationship to the Land.

God’s giving of the Land to Abram’s descendants doesn’t automatically resolve the difficult and complex problems of modern Israel and the West Bank. But being aware of the foundational claim of the Jewish people to the Land, the West Bank included, sure makes me feel a lot better about staying with my friend in Gilo.

Scriptures taken from the English Standard Version.