The Indivisible Scriptures (repost)

Note: I am reposting this article from August 2018, because it addresses one of the main reasons why I am offering my Old Testament course online this month. Register now here.

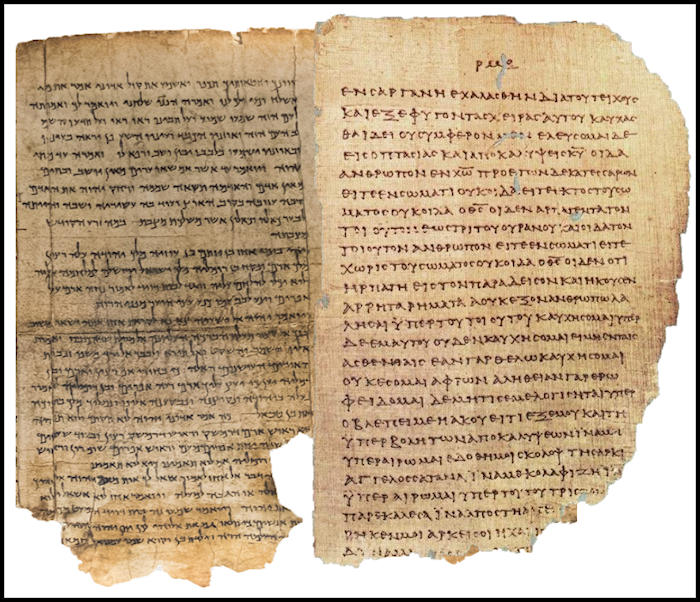

Hebrew & Greek biblical manuscripts

Download Audio [Right click link to download]

Scripture cannot be broken (John 10:35)

This past spring, popular megaplex church leader, Andy Stanley, presented a three-part sermon series, entitled “Aftermath,” described on his church’s website as: “Jesus’ resurrection launched a series of events that introduced the world to his new covenant and new hope. But old ways don’t easily give way. Not then. Not now.” In part three of the series Stanley claims that the early Jewish believers called for a sharp disconnect between the fledgling New Covenant community and the Hebrew Scriptures. Much can be said to critique Stanley’s approach and many of his specific statements, but what I wish to demonstrate here is that his attempt to undermine the ongoing authority of the whole Bible is not new. From the ancient heretic Marcion, who claimed the New Testament “god” was different from the Old Testament “god” to the Nazi-inspired “Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life” to Andy Stanley’s attempt to make Christianity “irresistible,” there have been all sorts of intentional schemes to tear the Hebrew Scriptures away from Christianity. While many believers immediately reject such anti-biblical ideologies, you may be surprised to discover how common negative views of the Old Testament really are.

Two gods?

Do you find how God is depicted in the Hebrew Scriptures overly harsh? If so, you may be further along the road to Marcionism than you may realize. Refusal to accept that the God who commanded Joshua to exterminate the nations of Canaan is the same God who through Jesus blessed little children and offers you forgiveness, then you may actually believe in two (non-existent) gods. The one God of the entire Bible may be difficult to understand, but not impossible. God himself succinctly expressed his complex and integrated character to Moses:

The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, but who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation. (Exodus 34:6-7)

“Merciful and gracious… but who will by no means clear the guilty.” God is both merciful and just. From Genesis to Revelation, God is always and forever consistent with himself.

Breaking an essential bond

We break the connection between Old and New Testaments every time we create illegitimate contrasts between them. For example, when Jesus’s words in the Sermon on the Mount, “You have heard that it was said to those of old” (Matthew 5:21, 27, 33, 38, 43), are taken to mean “You have heard that it was written to those of old,” that assumes that Jesus is contradicting, not interpreting, Moses. Is not twisting “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law (Torah) or the Prophets” (Matthew 5:17) into abolishing the Torah and the Prophets an attempt to unhitch the New from the Old? And this is in spite of what Jesus says in the second half of that same verse: “I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them”? “Fulfill” here cannot mean “to put an end to.” Rather, it indicates Jesus’s intention to demonstrate bringing the Hebrew Scriptures to their fulness by truly living them out and to equip others to do the same.

This would be a good place for me to clarify that there are indeed contrasts between the Testaments. How Scripture is to be understood and applied must be in light of our living in the Messianic age – these days of the New Covenant since Jesus’s coming. The Levitical sacrificial system is no longer in force nor is the Israelite theocracy, even though the sacrifice of the Messiah and his kingly role are central. The homogeneous makeup of Israel as the people of God has been extended to the ingrafting of the nations without the need of initiation rites. Yet this reconstitution of God’s covenant relationship to his people should not lead us to assume a casting away of the foundational function of Moses and the rest of the Hebrew Scriptures, not to mention the unconditional, eternal promises to Israel through Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

But doesn’t John chapter one, verse seventeen, for example, distance the New Testament from the Old? It reads: “For the law was given by Moses, but grace and truth came by Jesus Christ” This wording is found in the King James Bible and many other, though not all, popular English versions. But the “but” isn’t in the Greek. It was added in these translations, because the translators deemed it to be implied. The problem is that the implication may be more due to prejudice towards the Hebrew Scriptures than sound scholarship.

The addition of “but” in this verse fuels the law vs. grace false dichotomy. Christians have often taken Paul’s insistence on faith being the sole basis of God’s acceptance as necessarily devaluing the books of Moses and the rest of the Hebrew Scriptures. Paul was certainly concerned about an aspect of rabbinic teaching that regarded the embracing of Torah, not faith, as the sign of genuine covenant relationship with God. According to this traditional view, only born Jews and converts to Judaism can truly fulfill that role. The New Covenant opens the door to non-Jews to find full acceptance by God outside of the community of Israel. The term “law” in such contexts is a reference to the rabbinic system they erroneously assumed to be based on Torah, rather than the contents of the Books of Moses themselves.

Grace isn’t an exclusively New Covenant concept. Paul demonstrates that right relationship with God has always been established on the basis of grace through faith. The term, “grace,” is to be understood as God’s enabling power freely given to those who trust him, as reflected through all those who have been faithful to him from Abel onwards. The contrast between Moses and Jesus in John 1:17 is one of degree and application, hearkening back to Jesus’s words from Matthew about “fulfillment.” Grace doesn’t nullify the essential role of the Hebrew Scriptures. On the contrary, we can’t fully understand grace apart from it. Through Jesus the satanic oppression of sin is broken, thus enabling anyone anywhere to know the God of Israel and be filled with his Spirit. What was experienced by a few in a relatively small region of the world is now accessible to all everywhere through the New Covenant.

The Law as negative

Another way some disconnect the Hebrew Scriptures from the New Testament is even though they passionately value God’s Law, they do so only in a negative sense by focusing exclusively on how it demonstrates our need for God. Doesn’t Paul make a case for this?

Now we know that whatever the law says it speaks to those who are under the law, so that every mouth may be stopped, and the whole world may be held accountable to God. For by works of the law no human being will be justified in his sight, since through the law comes knowledge of sin. (Romans 3:19-20)

The Torah’s function in illuminating the human sin problem is core, but is that it? Is this all that’s behind these words from Paul to Timothy?

All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work (2 Timothy 3:16-17).

Are we made “complete” (meaning “mature”) and “equipped for every good work” by the Hebrew Scriptures showing us nothing but how sinful we are? You might think that’s why Paul told the Corinthians (see 1 Corinthians 10:1-13) that Israel’s failure in the wilderness should act as an example – a bad example – to them. If so, you may have negative prejudicial glasses on. Israel did act badly. But how do we know this was ungodly behavior except that the Books of Moses plus commentary from the Psalms inform us of such? Paul’s goal for the Corinthians wasn’t only that they wouldn’t follow the bad example. It was that they would act in the desired godly manner as revealed in these Torah stories. The effectiveness of these examples is that they reflect the reality of life and God’s will regardless of the time period.

This is what Paul is talking about when he reminds Timothy that “all Scripture” is essential for godly living – “all Scripture” meaning, as it did in the entire early church, the Hebrew Bible, since there was no New Testament yet. Not only did Paul regard the Hebrew Scriptures as effective, they were also sufficient. This may be difficult for many Christians to accept, due to how much they are ignored, with or without the negative sentiments I have outlined. This in no way downplays the inspiration and authority of the New Testament. Rather it emphasizes how foundational and effective the Hebrew Scriptures were (and should still be) for believers.

The “Old” Testament

Then there’s the title itself, “the Old Testament.” You likely have never thought about how this way of referring to it devalues it. First, Old rather than New automatically sounds negative to modern ears as in “Tired of the same Old Testament? Try the new and improved one!” Of course, that might be due to we moderns’ overly positive take on progress. Be that as it may, it doesn’t accurately describe this sacred collection. It’s misleading, in fact. While the Old Covenant (“testament” being another word for “covenant”) given through Moses at Mt. Sinai plays a central role in the Hebrew Scriptures, God’s revelation of truth in these writings isn’t limited to the covenantal arrangement itself.

There are obvious passages that are outside of the Sinai covenant. All of Genesis through Exodus chapter nineteen precede it. The Book of Job doesn’t have covenantal references nor do some of the prophetic messages given to non-Jewish nations. Even within the narrative context of the Sinai covenant itself and its specific directives (commandments), we discover universal truths about God and life that both predate and outlive it. This is why I prefer to use the term, “Hebrew Scriptures.”

The New Testament’s dependency on the Hebrew Scriptures

Finally, contrary to popular misconception, the New Testament doesn’t stand on its own. This is not to say that it can’t or should never be read on its own. It’s that it understands itself as being based on the Hebrew Scriptures. Not only is it filled with hundreds of direct quotes from, and allusions to, the older writings, the concepts of God, righteousness, sin, salvation, redemption, forgiveness, Messiah, the Holy Spirit, and on and on, are all deeply rooted in the Hebrew Scriptures. To read the New Testament apart from its scriptural context is to leave it open to great abuse and manipulation. To unhitch the Hebrew Scriptures from our faith is to cut ourselves loose from God himself.

Scriptures taken from the English Standard Version